Because my father Brig

Balbir Singh, MC, was from the Kumaon Regiment, I exercised parental claim and

was commissioned into 4 Kumaon on 20 Dec 1970 at the age of 19 ½ , a tall,

strapping, athletic lad with lots of brawn and perhaps not too much brains !! I

was then just a happy go lucky young teenager stepping into the adult world.

Perhaps I was aware of the

rumblings within East Pakistan and had heard of Tikka Khan and Mujibur Rehman,

but my concerns at that time was quite at ground level, about making a career

of infantry life. After a few days with my parents, I caught a train to the

east, and joined my Battalion that was at that time deployed in anti-insurgency

operations in Nagaland. Immediately on arrival at the Battalion HQ, I was sent

to an outpost in thick tropical jungle and got embroiled in patrols and

ambushes, fighting Naga rebels. Hence, I was quite unaware of the magnitude of

the exodus of the refugees and the volatile situation in East Pakistan. There

were no newspapers at my picket, but there was ‘All India Radio’ broadcasts

which I listened to on my personal ‘2 in 1’ transistor, for pure entertainment.

I confess that I was more interested those days on ‘Binaca Geet Mala’, a musical show broadcasted by ‘Radio Ceylon’

than the political turmoil and travails of the people of East Pakistan. From

discussions with my peer group and a few seniors, I did became aware that the

Indian Army may be called upon to intervene and that the overall situation was

deteriorating rapidly. The thought of going to war excited me, though I had no

clue as to what I was to do in such a war, if it did come about.

On 9 Sep 1971, my

Battalion, along with two other infantry battalions of 81 Mountain Brigade was

ordered to hand over our pickets in the jungles of Chekasang and immediately

move to Dhimapur. The fourth unit of the Brigade was ordered to stay back and

take over the job of the departing battalions, waylay the Nagas on their way to

China. Since the men of my battalion had been deployed on distant pickets for

more than a year, it was a welcome opportunity for us to meet one another and

make merry.

But our venerable

Commanding Officer, had

other plans for us. For the next month, we were drilled continuously on

infantry warfare, crossing water obstacles, patrolling behind enemy lines, frontal

assaults and field firing with light as well as heavy calibre infantry weapons.

The ‘Advance Party‘ of 4

Kumaon under the ‘Second-in-Command’ moved

by road to Sonakhira on 11 Oct 71. A special train was expeditiously loaded,

mostly at night, and we steamed out of Dhimapur during the early hours of 17

October 1971. It was ‘Diwali’, and the

young officers, generally referred to as ‘Gadhas’, drank ourselves silly,

played ‘Tin Patty’ and once in a

while fired our ‘Sten Guns’ upwards, out of the window of the moving train,

just for the heck of it. We were young, impetuous and having fun. It was time

for war, though the thought of war was most distant in my mind.

On 19 Oct, from Badarpur

the Unit proceeded in two different trains due to the weak section of railway

track and constant threat from enemy saboteurs. The railway line passed close

to the border and the Unit had its initial brush with enemy when the first

train was fired at by enemy snipers. However, no damage was caused and on 20

October the Battalion arrived at Sonakhira. We were then deployed in ‘Bagichara’

Tea Estate, with a rifle company each at Churaibari and Patharkandi. The ambush

on the train perhaps primed my mind towards war, that soldiering was about facing

bullets, and giving it back as good as one got it. However, there was much that

I had yet to learn.

All

of Oct 71, my Battalion remained at Sonakhira conducting intensive daily training

and preparing for offensive operations, same kind of things that we did at

Dhimapur. Quite frankly, as a Subaltern, I really did not understand what the

fuss was all about. In my opinion, we were a good fighting unit and perceived

that our CO was unjustly ruining our happiness by training us for what we were

already trained for. In retrospect, my Battalion and I could have trained for a

whole year and yet not been prepared for what was ahead of us, the apocalypse.

From conversations in the

mess tent and snatches of information exchanged by others, I became aware of

the setbacks suffered by Mukti Bahini as well as the Jats in the pre-emptive operations

at Dhalai and Atgram.

At one time, I heard that my Battalion was to stand by to relieve the Jats at

Dhalai, but it never came about. Rumours flew thick and fast, about the

impending operations against Pakistan Army (PA). It was almost certain the Unit

would very soon be involved in offensive operations. The town of ‘Juri’ in East

Pakistan was often mentioned as the likely objective of the Unit. Reconnaissance of Pak Army defences opposite

Kailashahar was carried out by young officers and Specialist Platoon

Commanders. The patrols were launched from ‘Kailashahar

Pocket’. This small salient had been captured in Mar 71, by Mukti Bahini

troops. The ‘Kailashahar Pocket’ had

a Mukti Bahini Check- Post, located in the Primary School. Atop the tin roof of

the Primary School building, fluttered a curious looking flag.

As the enemy was extremely sensitive to Indian Army (IA) movements, all

reconnaissance tasks were done with troops dressed in civilian clothes. Perhaps I looked like a Pathan rather

than a Sikh during those patrols.

At Sonakhira, I was ordered

to form a ‘Commando Platoon’ with a Section each from Rifle Companies with

Kumaoni troops (the Batalion had both Ahir and Kumaoni troops), along with few

local Bengali boys to act as scouts and ‘fighting pioneers’ (to carry head

loads of spare ammunition and combat stores). I was to carry out special

training of my Commando Platoon to conduct clandestine operations deep behind

enemy lines. Though I stuttered about with an ‘all knowing’ look, quite

frankly, the sum total of my knowledge about such an operation was confined to

training at NDA and in IMA, the ‘Great Escape’ variety. I did ask around and

got few sagacious tips from my illustrious Company Commanders. After this I went

about training the force under my command with zest, instilling a sense of

bonhomie and camaraderie amongst the disparate men who could not even talk each

other’s language. The Bengali boys, all of them about my age, were highly

motivated and enthusiastic to do anything and everything. We in turn tried to teach them the art of

handling heavy calibre weapons as well as clandestine operations. In a short

while, we integrated ourselves as an effective combat team.

On 25 Nov, a reconnaissance

patrol by the Commando Platoon that I led, had a narrow escape when it was engaged

by accurate Browning Machine Gun (BMG) fire from the enemy Border Outpost (BOP)

at Chatlapur. I had halted my ‘Commando Platoon’ in the midst of a ripening

paddy field near the IB to consume our haversack lunch. Perhaps we had strolled

into enemy territory like going on a picnic and the enemy had spotted us. The sharp

crack of machine gun bullets went over our heads and nothing untold happened. The

young Bengali pioneer ‘Mian Makbuddin’, who

was part of my team, was sharing my haversack lunch and trying to chat with me in

incomprehensible Bengali when the enemy opened fire. Quite sensibly, Makbuddin dived head-first into the

paddy field. The troops incredibly burst into spontaneous laughter. In utter

horror, the boy looked up to see the troops sitting calmly on the edge of the

field and laughing loudly, the bullets going above their heads. The troops were

more concerned with saving their lunch packets than worrying about the bullets

that had not yet hit their head. Looking at the older Kumaoni soldiers rolling

about in mirth, with haversack lunch packets in their hands, the young lad must

have thought all Indians were crazy. Perhaps it was really a strange reaction

to the first experience of being under enemy fire. Perhaps it was shell shock

or release of nervous tension. After repeated hearing of the fascinating

accounts of 47, 62 and 65 wars with Pakis, the real thing happening to us had

appeared rather unreal and even humorous !

Since we were still within our

own artillery range, over the radio set, I called the Unit Adjutant and

informed him about being under fire from the Paki BOP at Chatlapur and gave him

the map coordinates. After that I went back to eating my lunch. Soon there was

heavy shelling of enemy’s post by 75/24 mm field artillery guns located deep

within the Indian territory. The Pakis, to my relief, stopped firing at us. Through

my binoculars, I watched in fascination as some of the shells fell on the Paki

post and began obliterating it. Many of the other shells fired by our ‘Pea

Shooters’, rather blindly, exploded harmlessly in Manu River, well short of the

enemy post. The exploding shells sent up tall plumes of water, into the clear

blue sky. I had no idea how to give corrections to guide artillery fire. So I simply

gathered my bunch and went back to our base. Perhaps the purpose of my cross

border mission was to locate and destroy the enemy post, whose location was

unknown to my Battalion or Brigade. Perhaps the mission was successful. No one

told me, and I did not ask anyone. That is what a Subaltern was supposed to do,

I thought. He was not to ask stupid questions, but to just do and die.

On 26 Nov, orders were

received for my Battalion to move to its ‘Concentration

Area’, further south near Kailashahar Pocket. There was great excitement in

the air, as the battle procedure for offensive operations had commenced and

troops knew the long wait would be over. Soon the Unit would get to grips with

the enemy. Freshly honed skills of the men would be tested in actual combat.

The Battalion moved in convoy at 4.15 PM, from Sonakhira and reached ‘Assembly

Area’ after midnight. During the night-long move, Capt BS Jodha, our Unit Intelligence

Officer and I shared the cab of a lorry. As we wound our way over long dark

roads to Kailashahar, Jodha mentioned to me that we were indeed lucky to be

going into battle. For a while I was deep in thought about being ‘lucky to

going into battle’. I heaved a sigh and

rationalised that I would be ‘lucky’ if I lived to recount my personal experiences

in war, to wide eyed junior officers in future.

Upon our arrival at the Concentration Area on

27 Nov, Senior Company Commander Maj Dick Dhawan briefed the officers and JCOs

that the town of ‘Shamshernagar’ was to be the Unit’s objective. There was much

excitement in the air and maps were quickly opened and perused. The day was

spent in making preparations for offensive operations and the men were briefed

about their tasks. Combat loads, mostly ammunition, food and water, were

re-distributed and ‘Improvised Assault

Charges’ were prepared by Pioneer Platoon personnel and issued to the Rifle

Platoons. These Assault Charges were meant for destruction of enemy bunkers and

other fortifications in Shamshernagar.

On 28 November 1971,

General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the Infantry Division, Maj Gen Krishna Rao,

visited our location and gave us a stirring talk on the eve of battle. All personnel were seated on canvas tarpaulin

sheets and they listened intently as GOC reminded them of the Unit’s long

combat history. He said the Battalion was well prepared for the allotted

offensive task. GOC added that the Unit had been on active operations in

jungles of Nagaland for nearly two years and could not be better prepared to

tackle the allotted task of Capturing Shamshernagar. He reminded the men that

the Unit had won the ‘Best Battalion Trophy’ for outstanding combat operations

against Naga hostiles, out of the other 22 infantry battalions of the Division.

At the end of his speech, GOC light-heartedly remarked, ‘Since your objective is the town of Shamshernagar and name of your

Subedar Major is Shamsher Singh, I am certain your Paltan will be awarded

Battle Honour of Shamshernagar’. Perhaps it was a prophecy. Troops

cheered wildly and cries of ‘Bajrang Bali

ki Jai’ and ‘Kalika Mata ki Jai’

rent the air. Morale was high and men were eager to lock horns with the enemy.

After it was dark, the

soldiers hefted up the heavy packs onto their backs and the Battalion moved off

silently like heavily laden ghosts, through the sleeping town of Kailashahar.

The columns silently snaked their way to ‘Forward Assembly Area’. A few stray

dogs barked in the sleeping town as columns of troops silently passed through

the narrow lanes. By first light of 29 November, the Unit was deployed among

low hillocks adjoining Shamshernagar.

Shamshernagar was a

prosperous ‘Tea Town’, with large tea factories, and an airport linked by

regular Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) flights linking Dacca. Street

fighting is an infantry man’s nightmare and we knew that the enemy was waiting

for us. Intelligence reports gathered by Capt Jodha and higher formations indicated

that the enemy had made elaborate preparations to ward off an attack on

Shamshernagar. They had made extensive use of obstacles to strengthen the

defences, created a network of concrete bunkers with outer perimeter guarded by

several rows of bamboo ‘panji stakes’.

Automatic weapons had been sited on roof-tops, in sandbagged enclosures, with

overlapping field of fire. All told, even I, the youngest subaltern, knew that

a formidable battle awaited us.

The CO went off to confer

with the Brigade Commander and when he returned by lunch time on 29 Nov, he

called the officers and JCOs to give us an inkling of the overall Brigade

action plan. Shamshernagar was to be captured in two phases. In the first

phase, starting 30 Nov, 10 Mahar was to capture Chatlapur BOP & Tea Factory

while 3 Punjab was to capture No 9 Tila.

At the same time, our Battalion was to infiltrate a Company Group behind

enemy lines and establish a Road-block in Diggi Area, on the road from Shamshernagar

to Munshi Bazar, so as to isolate Shamshernagar and prevent any reinforcements approaching

from Munshi Bazar. In phase two, rest of our Battalion was to capture

Shamshernagar Town including the Railway Station, Tea Factory, Airfield,

Bridges over Manu River and the Katarkona Township. Even as a rookie subaltern, I could see that

it was an audacious plan, perhaps with similarities to Monty’s ‘Battle Of

Arnhem’ in WW-II, a battle plan that was taught in Indian military

establishments, perhaps as a foolish plan.

During

the briefing, specific tasks were given to the companies. Broadly, ‘A’ Company

Group under Maj YS Bisht, of which I was to be a part, was to infiltrate that

very night to establish the road black in Diggi Area. ‘D’ Company under Maj DK

Dhawan, was to occupy a position at Debalchara Tea Estate and hold it as ‘firm

base’ for the attack on Shamshernagar. Remainder of the Battalion was to build

up on the ‘firm base’ and attack Shamshernagar.

My Commando Platoon armed

with two 3” mortars and two 57 mm

Recoilless Rifles (in charge of Hav Mohan Singh), two 7.62 mm MMGs (in charge

of Hav Man Singh), the Kumaoni soldiers, a few ‘Fighting Porters’ from Pioneer

Corps and few local Bengali boys to carry additional mortar and MMG ammunition,

all of us were grouped with the ‘Road Block Force’ under Maj Bhist. The Road Block force moved from FAA on foot,

at about 4 PM on 29 Nov and reached

Border Security Force (BSF) picket named ‘Bolsip’ located on the IB,

after it was dark. CO, 2 IC, Adjutant and our Subedar Major arrived by jeep and

were waiting at Bolsip when the Road Block Force arrived on foot travelling

cross country in the dark. The CO and his party shook hands with all personnel and

last minute details were co-ordinated. At 7 PM, the heavily laden troops

silently crossed the IB and began to infiltrate behind the enemy line. I also

noticed that Lt Waki, a Mukti Bahini officer, along with a dozen Bengali

soldiers had joined us at Bolsip and were tagging along with us, under the

command of Maj Bhist.

Tea bushes on East Pakistan

side of the IB were tall and dense, as they had not been pruned for a long while.

The column inched forward, into the dark night, struggling through the tea

bushes, bypassing known enemy positions along the way. While inching forward,

one of my solders accidentally activated a trip-flare. The flare hissed loudly

and emitted a blinding, white light from its fiercely burning phosphorous tube.

Troops immediately hit the ground, crawled rapidly to whatever cover they could

find and lay very still. Almost immediately there were nervous shouts from a Paki

picket, located nearby on a raised mound. A long LMG burst was fired by the picket,

but the bullets went above our heads. Someone, probably a Paki JCO, screamed

choicest abuses at his men in Punjabi ordering them to stop firing, ‘Must be a

Dog’, he commented. The firing

stopped. We remained still for more than half an hour and then very cautiously resumed

our march. It was a very unnerving, yet an exciting experience.

By 3 AM, the Road Block Force

occupied a low knoll, which dominated the Shamsher Nagar – Kamalganj - Comilla

Highway. While Maj Bisht was reporting our position to the Adjutant on the

radio-set, our troops rested their heavy loads on the barrel of their weapons,

with the butt placed on the ground for support. 2 Lt MPS Khati and I quickly deployed

sentries and formed an ambush position. The lights of passing military vehicles

could be seen at regular intervals on the road below us.

Some men had even quietly slumped

to the ground to rest. Surprisingly, some soldiers even drifted into deep

slumber, unconcerned that they were behind enemy lines on a dangerous mission. Maj

Bisht passed orders for troops to wait for gaps between passing enemy vehicles

and swiftly cross the road, in twos and threes! Once executive orders had been

passed to cross the road, the sleeping soldiers were quietly awakened and they

promptly rose to their feet. There were a few abrupt halts while crossing the

road, when the lights of an unexpected vehicle were seen rapidly approaching.

By 4 AM, the road had been safely crossed and the leading scouts had neared a

rail bridge on the Sylhet- Comilla rail line that ran parallel to the road. The

bridge had armed sentry at either end, while other enemy soldiers were sleeping

in a nearby tent. Approaching silently through the heavy winter mist, the leading

elements of ‘A’ Company quickly overpowered both the surprised sentries. The

enemy troops within the tent were roused from their warm blankets, and swiftly

taken prisoner. After they had pulled on their boots, their wrists were bound with

line-bedding and the prisoners were sent to the rear of the infiltrating

column.

At

about 6 AM on 30 November, the column crossed the railway embankment and neared

the Road Block site. The pink hues of approaching dawn heralded an action

filled day – a day during which many soldiers would be killed on either side. Many

more would be wounded. It was to be a day of reckoning, and packed with action.

It was a day that would be well remembered for many years to come. Indian Army,

the Mukti Bahini as well as the Paki Army soldiers would perform extraordinary

feats of courage and valour. As daylight

increased, the raised alignment of the road running from Shamshernagar to

Munshi Bazar became visible, about a kilometre from where the column had

halted. After surveying the area through his binoculars, Maj YS Bisht ordered

the ‘road block’ to be established.

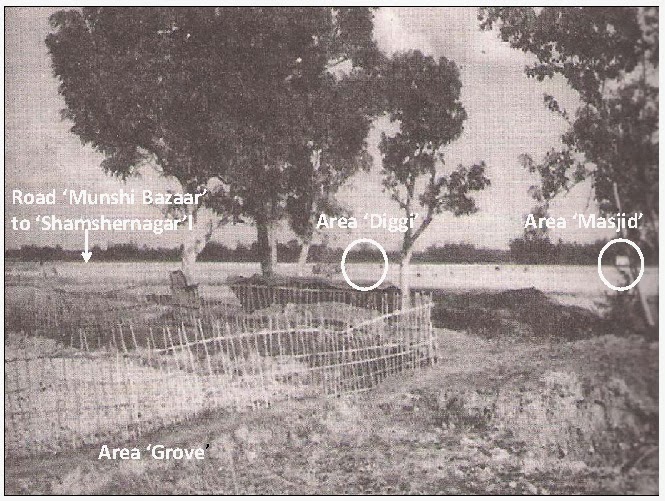

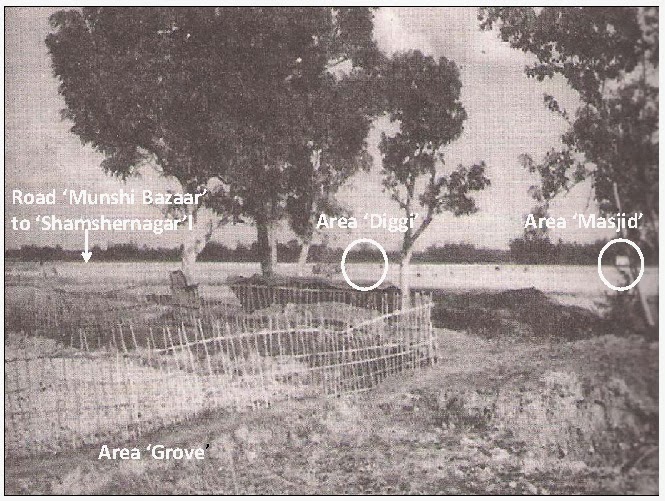

My Commando Platoon, Lt

Waki’s Mukti Bahini guerrilla section and No 2 Platoon led by a JCO were

ordered to advance through the fields of golden, ripening paddy and occupy ‘Masjid’ and ‘Diggi’ respectively. We were to face Shamshernagar and dominate the

road. In the mean while No1 Platoon and No 3 Platoon, directly under Bhist were

to take up positions at ‘Grove’ and

cover the road, facing Munshi Bazar. Company HQ and the Section comprising 3

inch mortars were to deploy at ‘Grove’.

While platoon commanders were being briefed for their tasks, troops sank to the

ground and rested their tired feet. Some industrious men opened their packs and

extracted their haversack breakfast. They consumed the packed ‘puris’, with great relish. After the

short halt, Platoon Commanders moved their troops towards the allotted

positions.

Both

‘Masjid’ and ‘Diggi’ were located on pieces of raised ground and they effectively

dominated the fields of ripening paddy. When my Commando Platoon and No 2

Platoon under Khati reached within about 200 mtrs of our objectives, we were

pinned down by intensive volley of automatic fire from the enemy. We hugged the

ground in the dry paddy field, but there was no cover. Over the din of firing,

I shouted at my Platoon to attack, rose and started running towards an enemy

BMG that was firing from near the ‘Masjid’.

I glanced back and it was an awesome sight to see my brave soldiers also rise

to their feet, under withering enemy fire and follow me. Half way, I yelled for the 57 mm recoilless

rifle (RCL) to be brought forward. Hav Mohan Singh and another jawan crawled

though the ripe paddy crop with the RCL gun and its ammunition. I pointed out

the enemy BMG, that was firing from behind a bush, on the left, immediately

adjacent to the ‘Masjid’, Hav Mohan

Singh took aim and fired the RCL gun with a loud blast. But the round went wide

and hit the ‘Masjid’.

I shouted at my small band

of men and we continued to engage the area with rifle and LMG fire. In the mean

while Hav Mohan Singh took better aim and fired. The second RCL round scored a

direct hit, destroying the enemy BMG gun pit. Other enemy soldiers were seen

running away. As they ran, they were cut down by accurate bursts of LMG fire

from my Commando Platoon. Immediately I formed my troops into a staggered

assault line and moved forward with our weapons on our hips. I ordered them to fire

at will and shots rang out from SLRs of my assaulting commandos.

In the meanwhile No 2

Platoon, had also risen from the paddy fields and they began their assault on

Diggi Area. Suddenly, out of nowhere bursts of enemy automatic fire swept them.

The Platoon commander, A JCO was thrown to the ground. His 2 i/c, also a JCO, was hit by a bullet.

Seeing both the JCOs go down, the platoon again went to ground and adopted

lying positions in the paddy field. However, the wounded JCO staggered to his

feet and shouted to the men to charge. Seeing them charge, the enemy abandoned

their positions and ran off. During the melee, No 2 Platoon Commander was shot

through the shoulder and his three Section Commanders were either killed or

wounded. Though we suffered heavy causalities, both platoons managed to secure

foot-holds on their respective objectives, and held on relentlessly.

By then, both the 3 inch

mortars had been deployed properly in ‘Grove’

and they began to rapidly engage the enemy. Hell seemed to have broken loose

and there was firing all around. With loud bangs, high explosive (HE) mortar

bombs began to explode around ‘Diggi’ and ‘Masjid’ as our BMG gun fire also swept

the area. Most of the enemy troops got up and ran back, but a few brave Pakistani

soldiers stood steadfast and faced the attackers.

After

a fierce close quarter fight with these enemy defenders, the two platoons

including mine, captured ‘Masjid’ and

two bunkers of ‘Diggi’. Enemy firing

continued unabated from the other two bunkers across the stretch of water. Meanwhile,

the main road from Munshi Bazar to Shamshernagar had come under the domination

of Road Block Force. By 9 AM, the A Company Group had suffered 19 casualties -

six soldiers were killed and 13 wounded. Meanwhile, enemy parties had begun to

work their way around the flanks of Road Block Force, in an effort to surround

and remove the serious threat.

Just then, an enemy convoy with

troops (probably reinforcements) was seen hurtling along the road and heading from

Munshi Bazar to Shamshernagar. The

convoy was led by an olive green coloured ‘Kaiser’ Jeep, that was followed by

two lorries loaded with troops. The two lorries were probably carrying reinforcements

to boost the enemy’s strength in Shamshernagar Area. Alerted by sounds of

firing, the enemy vehicles attempted to speed through the Road Block position.

With excited shouts, men of No 2 Platoon and my Commando Platoon engaged the

vehicles with all our weapons. Quite unbelievably, a HE bomb fired from a 2-inch

mortar exploded in the leading lorry that was loaded with troops. The lorry

careened off the road, caught fire and was completely destroyed. The direct hit

with a 2-inch mortar bomb was a stroke of good luck and the men cheered wildly

as the truck burned in a roadside ditch and sent up plumes of thick, black

smoke.

The explosion caused serious casualties and a number of enemy soldiers

were even flung off the burning lorry. The second lorry, that was following the

ill-fated one, ground to a halt and enemy soldiers jumped off and took up

firing positions on the road. From Area ‘Grove’, our MMGs fired long bursts

into the enemy troops as they were rapidly jumping from their lorry. The MMG

fire caused many more casualties. Heaps of dead bodies could be seen piling on

the road. Some enemy troops had taken up positions below the embankment and were

seen returning fire at our positions. They engaged us with 2-inch and 3- inch

mortar HE bombs. Huge columns of black smoke billowed up from the burning enemy

lorry, while the Kaiser jeep sped off towards Shamshernagar, leaving the enemy

leaderless. Despite this, the few enemy left alive rallied around their JCOs,

and started to crawl forward towards us using natural cover.

There was great expectancy when artillery fire was called from guns

located in India by Capt Dhanoa, FOO with ‘A’ Company. Soon, distant explosions

were heard as the in-coming shells fell almost 1800 - 2000 mtrs short of the

enemy positions and exploded harmlessly. Since the IA artillery guns had been

firing at maximum range, a chilling reality dawned on Dhanoa and rest of us

that we were far beyond the range of field artillery guns firing from

India. We had to now manage on our own,

that God only helped those who helped themselves.

The enemy’s determined efforts to continue the fight perhaps put our

Company Commander Maj Bisht into a quandary. He may have also been unnerved by

the fact that we had no artillery fire support, while the enemy could easily bring

a fusillade on our heads any time. He ordered me on radio to collect both

platoons, break contact with the enemy, and crawl back to Area ‘Grove’.

Shortly afterwards, firing from the enemy decreased, and the two the

platoons with me in trail began to crawl back through the flat and open paddy

fields. On seeing this movement, enemy soldiers charged, firing with all their

weapons, closing in for the kill.

With full knowledge that his actions would invite certain death, Sepoy Bishram Singh of No 2 Platoon, on his own

initiative, took position at ‘Diggi’, lying prone in firing position behind his

LMG and began to fire long bursts at the enemy to help cover the retreat of his

colleagues. While blazing away with the LMG, he was struck by enemy bullets in

the left shoulder and arm. Despite his wounds, this brave jawan kept the enemy

at bay, till he was sure that both platoons had occupied their new positions at

‘Grove’. Thereafter, the sounds of the LMG died out, perhaps he had exhausted

his ammunition. His stomach was ripped open by another well aimed burst of enemy

automatic fire and he was killed instantly. Sepoy Bishram Singh knew he could not

escape a fatal end when he volunteered to stay behind and cover the move of his

comrades. It was is HHHHHHII an

exceptional act of supreme courage. He knowingly gave up his life to allow his

comrades to retreat to Area ‘Grove’.

All day long our position at ‘Grove’

was subjected to enemy shelling by 120 mm mortars, from their positions at Shamsher

Nagar Airfield just north of us. The enemy also quickly brought reinforcements

from Maulvi Bazar / Munshi Bazar to launch two determined counter-attacks from

that direction. Due to our accurate fire from several quarters, and lack of any

sensible cover, the enemy suffered heavily during these counter-attacks and

withdrew towards Munshi Bazar to re-group. We had been fighting for many hours

and our men had almost run out of ammunition. To conserve precious ammunition, Maj

Bhist ordered the LMGs to engage the enemy with only ‘ single round’ fire. In

addition, all troops were given instructions to engage the enemy at the closest

range, so they were sure of hitting the targets.

The remnants of No 2 Platoon was by now under my command along with what

was left of my own Commando platoon besides remnants of the valiant Mukti

Bahini guerrilla section under Lt Waki, and what was left of the pioneers. Lt

Waki and his band of few guerrillas, as also the pioneers, had fought shoulder

to shoulder with us, equalling our own zest, grit, and valour, silently

suffering the depredations of war that we were all being subjected to. The

Mukti Bahini were different from my Kumaoni troops, as chalk is to cheese. But

in the heat of war, they had developed an uncanny camaraderie with my troops,

and we were equal brothers in arms, in every way. It is unfortunate that I

cannot remember their names now, all except Lt Waki.

We held our position with tenacity even when the enemy completely encircled

the ‘Grove’. Hav Hari Shankar, from No 2

Platoon, led from the front and fought off the advancing enemy with visibly raw

courage. Soon he was killed by a burst of fire in the chest and stomach.

I too was wounded, multiple injuries on both legs from shell fragments, but

crawled about from one gun position to other, partly to get first hand

appreciation of the situation, but mostly to cheer up my men. Right through the fighting, we managed to

drag the wounded backwards, and behind the cover of a bush where we had made a makeshift

medical post. Sep (NA) Muni Lal Mahato fearlessly moved about ‘Grove’ administering

morphine and lifesaving first-aid. A number of lives were saved by his selfless

devotion

& .

Around midday, one of our own fixed wing Air Observation Post (Air OP)

aircraft came above our position and circled about lazily in the sky. The enemy

stopped all bombardments perhaps to prevent discovery of their location by the

Air OP aircraft. They stopped paying attention to us and turned their ire

against the aircraft, engaging it with intense small arms automatic fire.

However, they soon gave up the effort as no damage was being inflicted. We used

this respite to regroup and tend to the wounded. After a while the aircraft

turned and went out of sight. Immediately the enemy started to pound the

‘Grove’ with 120 mm mortar fire. Like an Albatross, the aircraft reappeared,

well north of us, towards the airport. The enemy mortars fell silent once

again. We prayed for the aircraft to

stay, but soon it went away and we were back on the receiving end of the mortar

barrage.

At about 4 PM, the enemy

subjected our position to a concentrated severe mortar bombardment. About 300

bombs of 120 mm mortar exploded on ‘Grove’. The bombardment left the position

pock-marked with deep, smoking craters. Radio sets were destroyed and our communications

between A Company as well as with Brigade HQ within India were severed. The

vicious bombardment was followed by another fanatical counter-attack.

Fortunately for us, perhaps as a result of the good spotting by the Air OP

aircraft, the Brigade swiftly moved one 5.5 inch medium artillery gun well

forward near to BSF’s Bolsip post. This single arty gun started to engage the

enemy positions rapidly, but in a non-coordinated random manner. Though it did not do the enemy much harm, it

helped augment our morale. The enemy continued to rain mortar bombs into area

‘Grove’, while our medium artillery shells exploded in the paddy fields with

shattering bangs. Gunner S V Venugopalan, Artillery Radio Operator, performed a

splendid job of somehow repairing his radio set and made contact with the

single artillery gun position at Bolsip which continued with it’s fire support adding

to the melee at ‘Grove’.

Without any warning two mortar bombs exploded near me in rapid

succession. I was hit by more shrapnel and

flung onto my back. There was heavy dust in the air as I struggled to get back on

my feet. I felt a sharp pain at the back of my head, right wrist, elbow and my right

leg. Looking down, I saw that blood was beginning to seep through my shirt

sleeve as well as trouser leg, while drops of blood dripped from my head.

Realizing that I was wounded, I looked around and spotted Sep (NA) Muni Lal

Mahato. I beckoned to Mahato and asked him to speedily bandage my wounds before

the next salvo of bombs slammed into my position. As I was getting myself

bandaged, the enemy launched another counter-attack and some attackers nearly

broke into our defended position. I pushed Mahato away and staggered to the

front line.

Thereafter, savage hand-to hand fighting took place and the enemy was

stopped at the edge of ‘Grove’. Even the wounded men grabbed their weapons to

engage the charging enemy. In the heavy fighting, L Hav Man Singh (MMG Section

Commander), Hav Mohan Singh (RCL Section Commander) and nine OR were killed. The

ferocity of the enemy attack was such that besides me, within minutes, Khati

and nine ORs were also injured.

Sub Bhura Singh was wounded for the second time that day. Despite the setbacks,

the enemy was hurled back and they moved into distant head grows that were

beyond the range of MMG fire. Having observed the repeated enemy

counter-attacks being launched on Commando Platoon, Maj Bisht accompanied by

Sep Basant Singh (radio operator), dashed through heavy shelling and came to

Commando Platoon position at the forward edge of ‘Grove’. After brief

discussion with me, dousing me with reassurance and encouragement, he along

with his radio operator dashed all the way back to where he came from, right

through intense small arms fire. It was leadership at its best. I went back to

doing whatever I was doing, perhaps fighting for my life and that of those who

were under my charge, learning soldering as I went along !

L Nk Inder Singh (ex ‘D’ Company), a

Section Commander of Commando Platoon was directing the fire of his section

when a mortar bomb exploded near him . He was thrown about twenty feet into the

air and landed on me. I noticed that a piece of shrapnel had pierced his gullet

and Inder was desperately gasping for air.

Blood gushed out with every breath. In desperation, I tried to

unsuccessfully block the flow of blood with my thumb as more mortar bombs

exploded around us. Inder sucked in a long rasping breath and his eyes glazed

over. His lips turned pale as he died in my arms. Covered in blood, I handed Inder’s

dead body to Sep Ram Singh (Burmia). I was beset with uncontrolled anger.

Despite my wounds that debilitated me, I rushed to the defensive perimeter,

took over a LMG and began firing rapidly at the assaulting enemy, all the time

yelling and cursing, very volubly. It perhaps had a salutary effect on my team

and they too started shouting and cursing volubly and all of us together

brought intense fire on the enemy.

As 120 m HE mortar bombs were

raining down on ‘Grove’, through the dust haze I saw Sep Gokal Nand jump about

in pain and shock. His left arm had been severed above the elbow by mortar bomb

shrapnel and he was rapidly losing blood from the flailing stump. I wrestled Sep

Gokala Nand to the ground, ripped off his lanyard and wound it tightly around

the stump to stop the bleeding. Luckily, a lull in the incoming mortar bombs

permitted me to set the wounded Sep down in the bomb craters. Quite suddenly, I

felt dizzy from my own loss of blood and so I sat with a forward LMG detachment

and took some sips of water from a Sepoy’s water-bottle. Not giving up the

fight, the enemy remained at a safe distance and continued to fire at the

road-block position. After the day’s fighting, it was a great relief when the

sun began to set and shadows lengthened. The complete Area ‘Grove’ was pock

marked with craters, where enemy’s 120 mm (HE) mortar bombs had exploded during

the intense bombardment (around 300 bombs fell in about half an hour). Due to

my own serious injuries and loss of blood, I was feeling like a zombie.

By night fall, Venugopalan, the

Artillery Radio Operator, managed to repair one of the radio sets and patch

into the Brigade Net. The Brigade Major, I was told, passed instructions to Maj

Bisht, over the Artillery Radio Net, to return to India and re-join the

Battalion. Having successfully completed its task of creating a diversion and

preventing unrestricted induction of reinforcements that could have jeopardised

the capture of Shamsher Nagar, the ‘A’ Company Group was to now fight its way

out of the enemy’s encirclement and undertake the difficult trek back to India.

Just as Maj Bisht passed orders for the move through a runner, a fierce

enemy counter-attack drove a wedge between my troops and ‘A’ Company Group. To

find a safer ground, I had moved my troops and a small part of ‘A’ Company,

with most of the casualties from the ‘Grove’ to a large bamboo clump, towards

the railway line. During our move from ‘Grove’, we continued firing and had to

occasionally take ‘lying position’ behind the small embankments that bounded

the paddy fields. The movement was very slow since there were large number of

wounded men with me. In this process, I lost complete touch with Maj Bhist as

well as the A Company Group. Darkness surrounded us with an occasional para

flare that the enemy fired to locate us.

As there was no communication with

Maj Bisht, I was in a quandary, unsure of what to do. So I asked the wizened

old Senior JCO of ‘A’ Company, Sub Sultan Singh

what I should do. The SJCO shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘You are now in

command. Do as you please’. As a Subaltern that was perhaps the first time the

thought came to me that I could be in command. That life of so many, the good

name of my Unit, victory in war, the image of my country, all of it could be in

my young and inexperienced hands. I called Lt Waki, the only other officer with

me, though from Mukti Bahini, and ordered him to take four Sepoys with him to

reconnoitre, rendezvous with Maj Bhist if possible, and bring back orders for

me.

The enemy continued to fire at us,

rather blindly, and we continued to return the fire while Lt Waki ran off

towards the ‘Grove’. Waki returned in half an hour and reported that he had

seen large numbers of the enemy swarming over ‘Grove’. There was no trace of

Maj Bisht or ‘A’ Company. When the enemy began to fire at his party, Lt Waki

had quickly moved back to find me .

Having confirmed that Maj Bisht and ‘A’ Company had left the ‘Grove’, I gave

orders to my men to commence our retreat back into India. We had fought enough,

almost all were injured and there was no fight left in me because of the

pathetic condition of the wounded that included me. We picked up our gear and

weapns and moved off, almost backtracking the way we had come, with lesser wounded

persons helping the wounded. The stars were bright but it was pitch dark. We

moved in fits and starts, stopping often to evade what we thought were enemy.

Every hay stack, bund and tree appeared to be an enemy till we came close

enough to discern what it was. On many occasions we did encounter enemy search

parties. We went to ground, covered the mouth of the groaning wounded and

blended with the wheat and tea bushes. We did not fire any weapons even though

the enemy did, at random, to provoke us to fire back and reveal our position.

It was a remarkable night march, mostly crawling on our stomach, dragging the

wounded as well as heavy weapons behind us. All the more difficult because each

of us were wounded.

At around midnight, we came upon a

large enemy party in the tea gardens. A Paki officer had spread a map on the

bonnet of a Jeep, and was bending over it in the dim light of a hand held

torch-light, with three JCOs around him. The Paki soldiers were standing around

their vehicles in the darkness. The enemy was studying the map, trying to

assess the escape route taken by the columns of our Road Block force. Though my

instincts told me to spray the enemy with automatic fire, I realized the folly

of it. We went to ground and once again

played dead with our hands muffling the groans of the badly wounded and totally

exhausted men. After a while, the Pakis got back into their vehicles and roared

off in the opposite direction.

The return was torturously slow and the wounded kept moaning in pain. Slowly

the darkness was dispelled and the eastern sky began to light up. I was leading

the column when just before dawn I came upon a stone pillar. In the darkness, I

ran my fingers over the stone pillar. The deep inscriptions read ‘EAST PAKISTAN’.

On the other side of the pillar, the inscriptions read ‘INDIA’ followed by ‘BP’

and a number. I realized it was a ‘border pillar’ on the IB. Great joy and

relief spread through the column. The men quickly crossed to the Indian side

and sank to the ground, to rest.

The column had crossed the IB near

Bolsip BOP, close to the spot from where we had entered East Pakistan. With

some difficulty I got the men were back on their feet and the party moved on in

the cold, early morning darkness. They found a field telephone line and

followed it to the BSF Post at Bolsip. The surprised BSF sentries opened fire

on our party, mistaking us to be an enemy patrol. After shouted

identifications, the firing stopped. Fortunately, there were no further

casualties or injuries due to friendly fire. The BSF post was very hospitable

and they made us as comfortable as they could including the customary cup of

tea for all. Using the field telephone at the post, I informed Maj Pandit, the Brigade

Major (BM), about our return to India. BM wanted to know the details of the

road-block action and the whereabouts of Maj Bisht’s group. I asked for an

ambulance, and informed him that almost everyone with me, including me were wounded.

Promptly, vehicles were sent to Bolsip BOP and wounded personnel were admitted

to ADS.

On 1 Dec, our ‘Road Block’ action figured in news bulletin on Radio

Pakistan. They claimed that a rogue Battalion of Indian Army had penetrated

deep to the south west of Shamshad Nagar and that a Paki Brigade had

annihilated the Indian Battalion with loss of 40 Paki lives. They did not say

how many Pakis were injured. The Paki

radio broadcast made my CO smile, though our situation at that time was grim. My

CO was fond of saying that each soldier in 4 Kumaon was equal to four Paki

soldiers. So perhaps he was right, ‘A’ Company of Maj Bhist must indeed have seemed

like a Battalion to the Pakis. In the Road Block operation, A Company lost 21

men and 32 were wounded. The Road Block Operation helped the Brigade capture

Shamshad Nagar and move on to Sylhet, with 4 Kumaon in the vanguard.

Afterwards, for more than four decades I have often wondered what was

the purpose and what did we achieve in the Road Block Action - in the overall

context of that war to liberate Bangladesh. It is now certain that long before

the war began, Lt Gen Sagat Singh, the IV Corps Commander, had already figured

out in his mind how he was going to Liberate Bangladesh, by the blitzkrieg from

Ashuganj, Narsingdi, hopping right over the mighty Meghna river using

helicopters, onwards to Tungi and Dacca.

But to achieve that strategy, he perhaps had to draw the Pak Army into a

forward defence and neutralise them, to prevent them from running back to

Dacca. So perhaps Sylhet was to be mother of all battles and before he reached

Sylhet he had to go through the door at Shamshad Nagar. And the back door key

to Shamshad Nagar was perhaps in the hands of Maj Bhist and his ‘A’ Company

Group of 4 Kumaon. Though I am in a

wheelchair now, because of the injuries sustained at the ‘Grove’ that became a

bother in old age, I am glad I helped Maj Bhist close and lock the backdoor and

hold on to that key along with my brave Commando Platoon and the mighty Mukti

Bahini guerrillas of Lt Waki. Besides, I

could not have asked for a better ‘battle inoculation’ that led to a very

adventurous and long military career. Maj Bhist and I, along with the other

officers and men of 4 Kumaon continued to fight at Shamesher Nagar and

afterwards the mother of all battles at Sylhet. But that is another story. But

by then I had become a seasoned combat veteran from the ‘Battle of ruddy Grove’

!!

If I were young once again, I would perhaps like to go and do it all

over again.

FOOT NOTES

1.

My CO at that time was Lt Col Lakha Singh. The 2i/c was Maj DPS

Raghuvanshi. Maj BK Sharma was the Adjutant. The Company Commanders were Maj YS

Bisht, Maj Mahendra Singh, Maj Narendra Singh, Maj ID Khare and Maj DK Dhawan, SM.

Capt HC Sah, 2nd Lt MPS Khati, 2nd Lt BS Rawat, 2nd

Lt RS Sandhu, 2nd Lt BS Jodha, 2nd Lt Virendra Singh were

the other officers with me in 4 Kumaon during 71 war.

Under

the supervision of Maj Dick Dhawan, senior ‘Company Commander’

The

GOC’s predictions came true!, 4 Kumaon was later awarded ‘Battle Honour of

Shamshernagar’.

Hav Mohan

Singh (the RCL Hav) had a close physical resemblance with Hollywood actor Omar

Sharif. In the unit he was always jokingly called ‘Omar Sharif’. Mohan Singh was killed during fighting, later

in the day, along with Hav Man Singh (the MMG Hav).

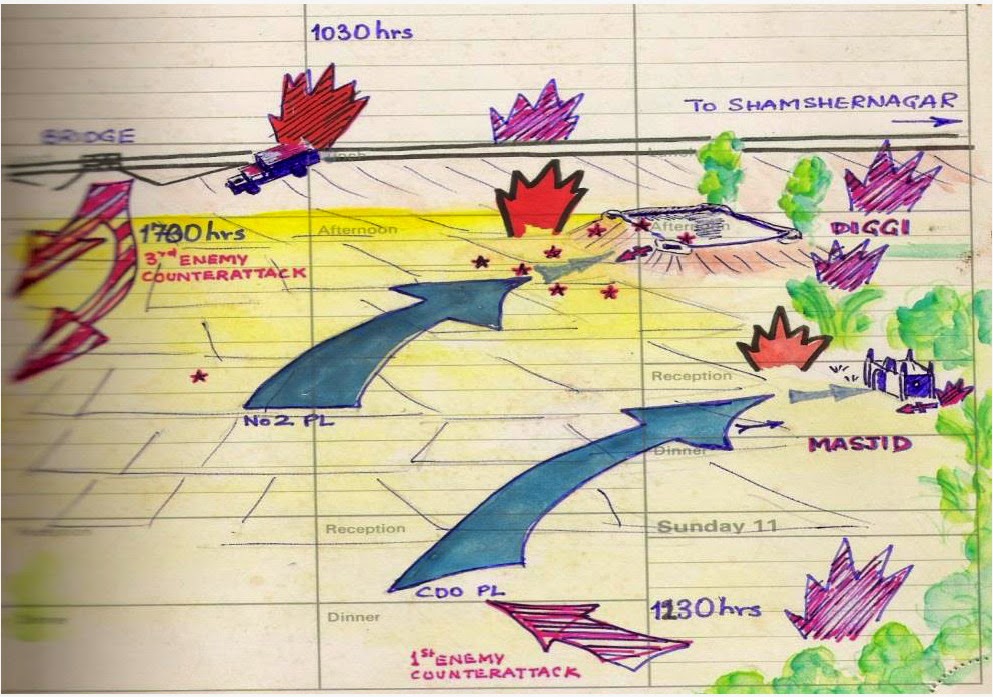

Sometime while

I was growing up at RIMC, my father presented me with an Agfa Click –III

camera, which tuned me into a keen photographer. I carried the Click-III with

me everywhere, right through NDA, IMA and into war. The pictures are from that

Clcik –III, taken at random during breaks in action. I also do water colour

paintings and the illustrations were done from memory, immediately after the

war.

Hav Hari Shankar’s son was born after his father had been killed at

‘Diggi’. He followed in his father’s

footsteps and today serves with honour in the same ‘A’ Company of 4 Kumaon.

A week later, my Battalion was ordered to advance from Shamsher Nagar to

Maulvibazar. On the way we stopped at the Road Block site. The dead bodies of

15 comrades killed during the fierce fighting were recovered from the paddy

fields – they lay where they had fallen. Sep Bishram Singh’s body was found at

‘Diggi’ with deep gashes in the stomach, caused by bursts of automatic fire.

His LMG had been removed by the enemy. The dead bodies were collected from Road

Block site by Sub Maj Shamsher Singh and cremated with military honours at

Kailashahar. Sepoy Bishram Singh was later awarded a posthumous ‘Sena Medal’

(SM).

2 Lt (later Maj) MPS Khati was severely wounded

in the enemy mortar firing. His father (Sub Bhopal Singh) had served in the

Unit during World War II in Malaya and Singapore. After the war Khati was

transferred to 2 Naga, where he met an untimely end in a road accident in 1988,

between Pathankot and Yol.

Later Maj Bisht briefed me that he had made every

effort to find me. And when he could not, he presumed that I was dead. He then

took ‘A’ Company and moved deeper into

enemy territory, towards Munshibazar, before starting their ex-filtration back

to India.

A Company

Group under Maj Bisht also

reached India safely, at BSF’s Bolsip post after a few hours. He too had a

similar and perhaps more arduous return journey.